Home > Insights & news > The Allens handbook on takeovers in Australia > Schemes of arrangement (for companies)

Schemes of arrangement (for companies)

- A scheme of arrangement can be used only for a friendly acquisition of a company, and is frequently used to effect 100% acquisitions.

- A scheme of arrangement is a shareholder and court-approved statutory arrangement between a company and its shareholders that becomes binding on all shareholders by operation of law.

- Schemes are subject to fewer prescriptive rules than takeover bids and therefore can be more flexible, but are supervised by ASIC and the courts.

- A standard scheme involves:

- a scheme implementation agreement between the bidder and the target;

- the preparation by the target, with input from the bidder, of a draft ‘scheme booklet’ which is given to ASIC for review;

- the target seeking court approval for the despatch of the scheme booklet to target shareholders and court orders for the convening of the shareholders’ meeting to vote on the scheme (ie. the scheme meeting);

- holding the scheme meeting;

- the target seeking court approval for the implementation of the scheme;

- implementing the scheme; and

- de-listing the target from ASX.

8.1 What is a scheme of arrangement

In general terms, a scheme of arrangement is a shareholder and court-approved statutory arrangement between a company and its shareholders that becomes binding on all shareholders by operation of Part 5.1 of the Corporations Act. The scheme structure can be used to reconstruct a company’s share capital, assets or liabilities. The structure can also be used to effect a compromise between a company and its creditors (which includes option holders).

The scheme structure is frequently used to effect an acquisition of 100% of the shares in a target company. In fact, in a friendly deal the scheme structure is more often used than the takeover bid structure. This is largely because of its ‘all-or-nothing’ outcome and the potentially lower target shareholder approval threshold (see section 6.2). A scheme acquisition may be done by way of a cancellation scheme (ie. all shares not held by the bidder are cancelled in exchange for the scheme consideration) or a transfer scheme (ie. all shares not held by the bidder are transferred to the bidder in exchange for the scheme consideration). The transfer scheme is the more commonly used type. As the bidder is not a party to the scheme, the court will usually require or expect the bidder to execute a deed poll in favour of target shareholders undertaking to pay the scheme consideration (ie. the purchase consideration) to them upon implementation.

Unlike a takeover bid, a scheme can only be used for a friendly transaction, because it is the target (not the bidder) that is required to produce and send to target shareholders a document containing the scheme proposal and certain other statutory information. Also, it is the target which applies to the court for orders convening the meeting(s) of its shareholders to vote on the scheme. Following shareholder and court approvals, the scheme will be implemented, resulting in the bidder owning 100% of the shares in the target.

This section 8 focuses on the key scheme of arrangement rules and features. See sections 10 and 11 for a discussion of the strategic considerations involved in planning or responding to a takeover proposal.

8.2 Indicative timetable

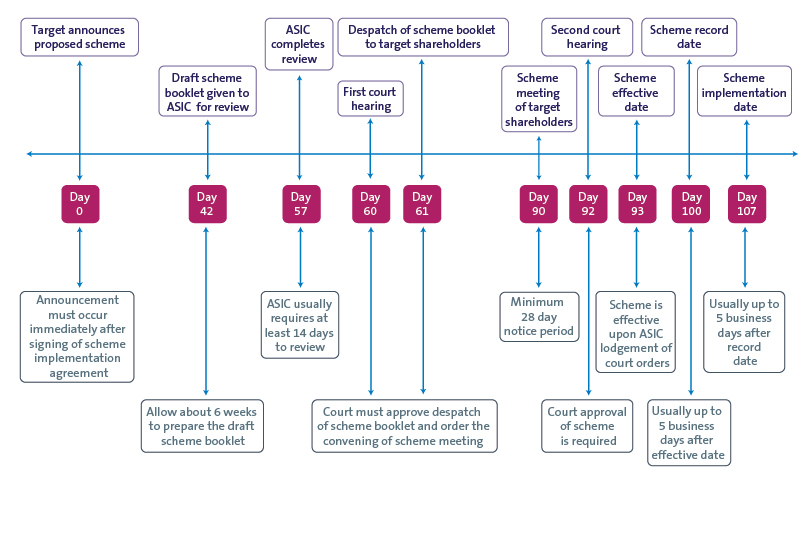

Below is an indicative timetable for a basic scheme of arrangement, which assumes that the scheme is successful, that there is no rival bidder and there are no regulatory actions that will affect timing.

8.3 Key scheme rules and features

The rules in Part 5.1 of the Corporations Act governing a scheme of arrangement are not as prescriptive as those contained in Chapter 6 for a takeover bid. Many of the rules applying to a takeover bid do not apply to a scheme. However, the Part 5.1 scheme rules need to be read in light of the numerous court decisions regarding schemes, as well as ASIC policies, which more or less seek to reflect the fundamental takeovers principles (see section 1.4).

Below is a summary of the key features of a scheme transaction, having regard to the scheme rules.

(a) Scheme implementation agreement

While not required by law, it is universal practice for a bidder and target to enter into an implementation agreement in respect of a scheme. This is because the proposal and implementation of a scheme requires a joint bidder-target effort. In contrast, a takeover bid involves the bidder and target undertaking discrete roles with specific areas of responsibility.

A scheme implementation agreement will usually contain: the target board’s obligations to pursue and recommend the scheme, the target’s obligations to apply to the court for an order convening a shareholders’ meeting to vote on the scheme, the scheme purchase consideration, the bidder’s obligations to provide the scheme consideration and assist with the preparation of the scheme booklet to target shareholders, the conditions to the scheme, and various other provisions dealing with operation of the target prior to scheme implementation. It is also common for a scheme implementation agreement to contain deal protection mechanisms such as exclusivity provisions (including ‘no-shop’ and ‘no-talk’ restrictions), rights to match rival bidders and a break fee payable by the target to the bidder in certain circumstances if the scheme is not successful.

For the most part, scheme implementation agreements and schemes can contain whatever provisions are agreed between the parties. However, there are certain matters which ASIC and the court will have regard to when giving their approvals. For instance, deal protection mechanisms generally need to comply with Takeovers Panel policy (eg no-talk restrictions need to be subject to an exclusion to enable superior proposals to be considered and recommended, and a break fee cannot normally exceed 1% of the target’s equity value).

In respect of a scheme implementation agreement, the regulatory focus is on disclosure. For instance, there needs to be adequate disclosure of any conditions to a scheme and of any matter known to the bidder or target that can affect the likelihood of implementation of the scheme. Note, though, that unlike for takeover bids, scheme conditions can be self-triggering (eg a due diligence condition is permitted). However, it is uncommon for targets to agree to such conditions.

The signing of a scheme implementation agreement triggers an obligation on an ASX-listed target to make a market announcement. The form of announcement should be agreed in advance between the bidder and target. Normally, a scheme announcement will contain the key terms and conditions of the proposed scheme, the target board’s recommendation that shareholders vote in favour of the scheme in the absence of a superior proposal (and sometimes also subject to an independent expert concluding that the scheme is in the best interests of target shareholders), and an indicative timetable. It is also common for the scheme implementation agreement to be publicly released in its entirety.

(Note: a scheme implementation agreement is binding only on the target and not on target shareholders. Only if and when a scheme is approved by shareholders and then the court does the scheme become binding on target shareholders.)

(b) Scheme booklet

After the scheme implementation agreement is signed, the parties complete preparation of the explanatory memorandum (usually referred to as a scheme booklet) which the target is required by law to send to its shareholders in advance of the scheme vote. A scheme booklet must contain information about the scheme, the target directors’ recommendation and other disclosures – effectively it must contain the same information that would be in a bidder’s statement and a target’s statement if the transaction were effected via a takeover bid instead. The scheme booklet must contain information supplied by both the bidder and target – hence the need for the target to ensure the scheme implementation agreement obliges the bidder to provide the requisite information.

It is also common practice, and expected by ASIC and the court, for a scheme booklet to include or be accompanied by an independent expert’s report commissioned by the target which states whether, in the expert’s opinion, the scheme is in the best interests of target shareholders. There is a statutory requirement for the target to commission an independent expert’s report where the bidder’s voting power in the target is 30% or more, or a director of the bidder is also a director of the target.

ASIC must be given a reasonable opportunity to review and effectively approve the scheme booklet – it usually requires a review period of at least 14 days.

(c) First court hearing

Following ASIC’s review of the scheme booklet, the target must apply to the court for orders to approve the despatch of the scheme booklet and the convening of the scheme shareholders’ meeting(s). If there is more than one class of target shareholders for the purposes of the scheme, each class must vote separately on the scheme (see paragraph (e) below on scheme classes).

The court cannot make those orders unless ASIC has been given at least 14 days’ notice of the court hearing and the court is satisfied that ASIC has had a reasonable opportunity to examine the proposed scheme and scheme booklet, and to make submissions on those.

(d) Scheme meeting

The meeting of target shareholders to vote on the scheme (ie. the scheme meeting) is usually held about 28 days after the despatch of the scheme booklet. For the scheme to be approved by shareholders, it must be approved at meetings of each ‘class’ of shareholders as follows:

- the scheme must be approved by a majority in number of the target shareholders in the relevant class who have cast votes on the resolution (but note that the court has the power to waive this requirement); and

- the scheme must also be approved by 75% or more of the votes cast on the resolution by target shareholders in the relevant class.

If the bidder or its associates hold any target shares, they must usually either refrain from voting or vote in a separate class. The practice is for the bidder and its associates to refrain from voting.

See paragraph (e) below on scheme classes.

(e) Scheme classes

The requirement for a scheme to be approved by each class of shareholders makes the formation of classes of utmost importance.

The rule is that, for the purposes of a scheme, a class of shareholders are those ‘whose rights are not so dissimilar as to make it impossible for them to consult together with a view to a common interest.’ This involves an analysis of: the rights against the company which are to be affected by the scheme; and the new rights (if any) which the scheme gives, by way of compromise or arrangement, to those whose rights are to be so affected.

The concept of scheme classes should not be confused with classes of shares. In a scheme context, different classes can arise as between shareholders who hold the same type of share (eg ordinary share). This is because a scheme can potentially confer different benefits on different shareholders. A clear-cut example of the creation of scheme classes is where one set of target shareholders is offered a specific type of scheme consideration (say, shares in the bidder) whereas all other shareholders are offered cash only. This is allowed in a scheme as the collateral benefits rule in takeover bids does not apply to schemes. Differential consideration is not possible in a takeover bid given the collateral benefits rule plus the requirement that all offers must be the same.

But it is rarely this straightforward. There are often complex questions of whether scheme classes arise where one target shareholder has entered into an arrangement with the bidder that is separate from, but conditional upon, the scheme (eg an asset sale). The general principle ought to be that where the separate arrangement is struck on demostrably arm’s-length terms there is unlikely to be a class issue, though this has yet to be properly tested as the practice has been for target shareholders who are party to a ‘side deal’ with the bidder to abstain from voting on the scheme.

The creation of separate classes can be problematic because it gives each class of shareholders an effective veto right over the scheme.

Even where there are no separate classes, a Court may take into account the fact that particular target shareholders have extraneous commercial interests when exercising the court’s discretion in deciding whether to approve a scheme. The Court can, as part of its fairness discretion, disregard the votes of target shareholders with extraneous interests.

(f) Second court hearing

If the scheme is approved by target shareholders and all scheme conditions have been satisfied or waived, the target returns to court for an order approving the scheme. The court hearing usually occurs within a day or two after the scheme meeting.

At that second court hearing the court does have a discretion to refuse to approve the scheme. The courts are normally reluctant to impose their own commercial judgment in relation to a scheme that has been approved by shareholders, except in very limited circumstances such as where the relevant scheme offends public policy. However, courts are not permitted to approve a scheme unless: it is satisfied that the scheme has not been proposed for the purpose of avoiding the requirements of Chapter 6 (ie. to avoid using the takeover bid structure), or ASIC issues a no-objection statement.

(g) Effective date and implementation

If the scheme is approved by the court, it takes effect upon lodgement of the court order with ASIC. There is normally a period of up to 2 weeks between the day the scheme becomes effective and the date it is implemented. This is to allow time for the target to close its register, ascertain which persons are registered shareholders as at the record date (usually up to 1 week before the implementation date) and prepare for the provision of scheme consideration. On the implementation date:

- all of the target shares other than those held by the bidder are transferred to the bidder (in a transfer scheme) or cancelled (in a cancellation scheme); and

- the scheme consideration is provided to target shareholders – if it comprises cash this occurs via the despatch of cheques or the electronic transfer of funds into nominated bank accounts, and it if comprises securities this occurs via the issue of those securities.

(h) De-listing

Following scheme implementation the target is then delisted on a date determined by the ASX upon application by the target – normally no more than a few days after the implementation date.

(i) Liability regime

Unlike for takeover bids there is no specific liability regime for scheme booklet disclosures. Rather, a scheme booklet is subject to the general misleading or deceptive conduct provisions in the Corporations Act.

Under those provisions, if there is a statement or omission in the scheme booklet that is misleading or deceptive, any person who suffers loss or damage as a result can recover the loss or damage from the person who breached the obligation. There is no specific defence to liability but a person can seek relief from the court from liability to pay compensation on the basis that the person acted honestly and, having regard to all the circumstances, ought fairly to be excused for the breach.

The target company has primary liability for a scheme booklet, though any person who was involved in a breach of the misleading and deceptive conduct provisions will bear liability (eg the bidder will usually bear liability for bidder-provided information). Despite the absence of statutory defences, the directors of a target company and bidder company can, in practice, substantially reduce their liability exposure by establishing a due diligence and verification system similar to that devised for takeover bid documents. Courts expect that target companies, as well as bidder entities, will have established and implemented such systems.

Collaborating for economic growth

In times of economic uncertainty, banks play a key role in fostering growth.

Get in touch

Allens is an independent partnership operating in alliance with Linklaters LLP. © 2020 Allens, Australia